Growing up, I always grabbed the daily newspaper to flip to the comic pages. We all had our favorites: Peanuts, Garfield, Calvin and Hobbes. They all brought a hint of a smile as we read through the punchlines.

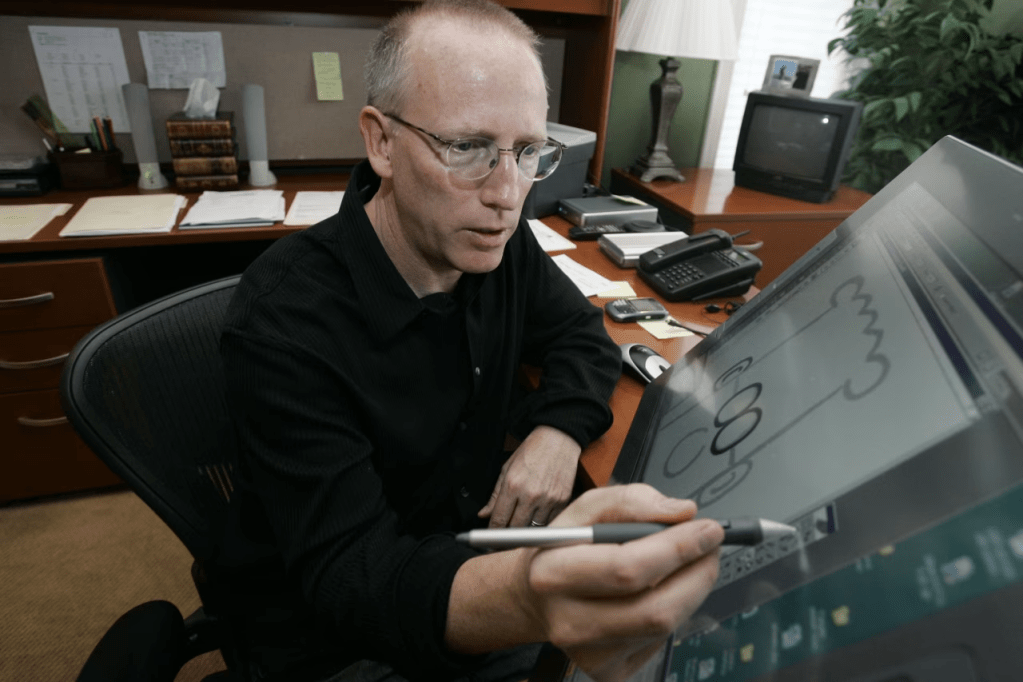

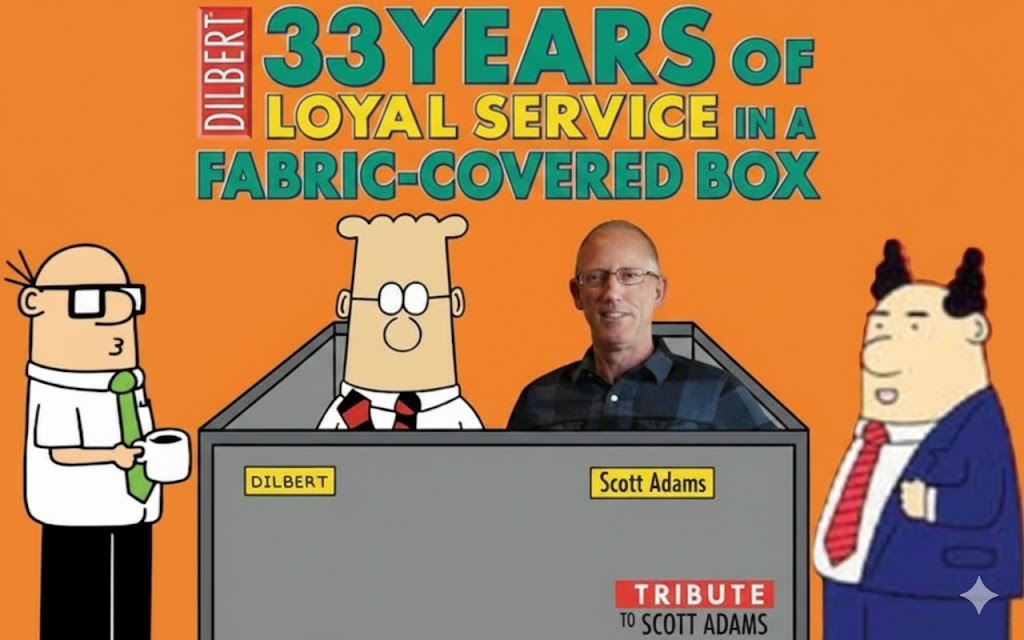

Today, I want to honor Scott Adams, who made me smile and laugh more times than I can count during my working career. Adams was the creator of Dilbert and the grandmaster of office humor. He passed away at age 68 on January 13th.

The three or four panel comic strip is a masterclass in efficiency. Unlike a movie or a stand-up routine, a strip must tell a complete story. Beginning, middle, and end, in about five seconds of reading time. It’s hard to believe how much pleasure these simple drawings have given me over the years.

I think of the comic strip as the grandfather of the humor we see on social media today: the one-liner “Dad jokes,” or the talking dogs poking fun at their owners. It’s a setup and a punchline, all within seconds. Before the internet, we had daily comics.

In many ways, this “short” joke setup is the hardest to master. There is no time to warm up the audience; the humor must be instant.

Over the last few years, I have started my version of a treasure hunt. I’ve been collecting the 50 published Dilbert books. I’ll pop into a thrift store and scour the used books to see if there are any I’m missing. For me, it’s about the hunt as much as the having. As of today, I am missing only one of the 50 books. Number 34, I am coming for you.

When I heard of Scott’s passing, I went back to read some of the early strips to celebrate his work. Dilbert started in 1989. At its peak, it was in 2,000 newspapers across 70 countries and published in 25 languages. It reached an estimated 150 million people. It was a global phenomenon.

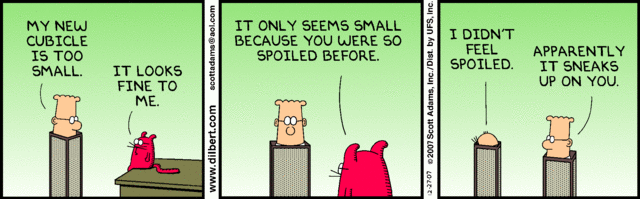

The personal computer revolution of the ’80s led to an explosion of people moving into offices. The cubicle was a way to pack more people into less space, reconfigurable as staff were hired or fired. As the ’90s continued, the cubicles got smaller and smaller until the walls disappeared entirely for “open concept” offices.

Nothing defines the human predicament more than the cubicle.” — Scott Adams

Pure torture, in my opinion. The open office makes you miss the “good old” cubicle. When you step back and look at our daily lives in a fabric-clothed box, we were begging for someone to make fun of us.

Scott Adams was that person. He struck a nerve because he captured the small, agonizing moments of our workdays. He was the first to poke fun at the corporate world in a way that hit home. He skewered lazy coworkers, sadistic bosses, weird HR rules, and the inane corporate “flavor of the month.” He understood how crazy our work world truly was.

Adams started Dilbert from his own cubicle. He worked at Pacific Bell from 1986 to 1995 as an applications engineer and budget analyst. He often sat in boring meetings, sketching his boss and coworkers. The office was a constant source of “inspiration” for characters and situations he put into the strip.

I worked at a “phone-like” company early in my career, and it was hilarious relating my daily life to his writing. It was ironic the day we started a new Quality program and that day the Dilbert was about Six sigma (a quality program). I was one of millions who saw my own workplace reflected in his.

Interestingly, Adams was an economist with an MBA—not what you’d expect for an artist. But he had always dreamed of being a cartoonist. When he was nine years old, he sent a letter and some drawings to Charles Schulz (who drew Peanuts), asking for advice. To Adams’ surprise, Schulz wrote back a kind, encouraging letter. Adams framed and kept that letter his entire life, citing it as the moment he truly believed a career in cartooning was possible.

Adams was also a famous proponent of daily affirmations. Starting in the late ’80s, while still at Pacific Bell, he would write the same sentence 15 times a day: “I, Scott Adams, will be a famous cartoonist.” He didn’t just think about it. He physically wrote it. He chose “famous cartoonist” because it was a specific, measurable outcome. By writing it daily, he “programmed” his brain to look for opportunities he might otherwise have ignored.

In 1997, when Scott Adams won the Reuben Award (the highest honor in cartooning), Charles Schulz himself presented it to him. It was a full circle moment, receiving the industry’s top prize from the man who had encouraged him 30 years earlier.

The two men were similar in their cartoon themes. Schulz’s Peanuts dealt with the “quiet” loneliness of childhood, while Adams’ Dilbert captured the isolation of the modern cubicle and nerd culture. Schulz was one of the first and greatest of the newspaper era drawing for 50 years. Adams, drawing Dilbert for 33 years, is likely one of the last, as newspapers fade away.

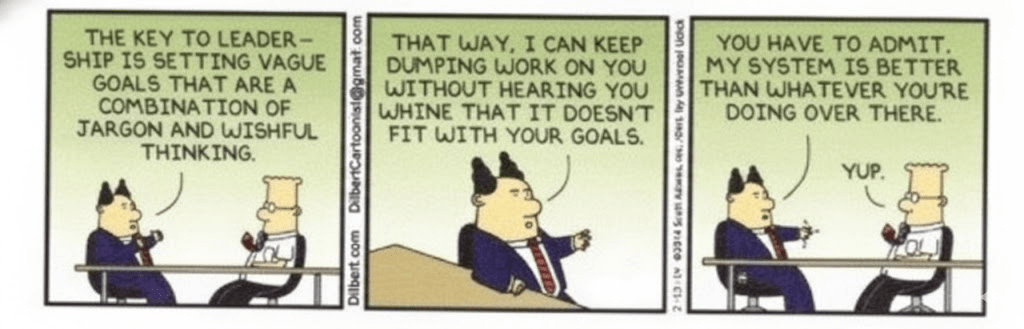

Outside of the strip, Adams was well known for promoting “Systems Thinking.” He argued that systems are better than goals for long-term success. A goal is an objective you either reach or you don’t (e.g., “lose 20 pounds”), while a system is something you do regularly to increase your odds of happiness (e.g., “eat right every day”).

He argued that goal-oriented people live in a state of continuous failure until they reach the goal, then feel empty once it’s gone. System-oriented people succeed every time they apply their system. This is very similar to James Clear’s approach in Atomic Habits.

I try to take this systematic approach in my own life. I want to be a writer, so I set aside time every morning to write. If I want to be fit, I exercise before work. It’s the system that gets you there, not the goal.

On this blog, I often explore the “dark side” and the mental health challenges people face. To truly honor Scott Adams, we have to acknowledge the mental toll he likely faced in his career

For 33 years, Adams produced a joke every single day. Deadlines could not be missed

He didn’t have an assistant; he didn’t have a writers’ room. He sat in his own ‘fabric-clothed box’ at home so that he could make us laugh about our cubicle at work. While that level of isolation takes a toll, it also produced jokes that connected millions of strangers.

He developed a medical condition that cost him his voice for several years. This cut him off from the world even more. He became even more of a self-proclaimed hermit due to his condition.

Think about the COVID lockdowns, but lasting for 30 years. It takes a rare kind of mental fortitude to spend 30 years in solitude just to ensure the rest of us had something to laugh at during our lunch breaks. I look at that level of solitude and see the potential for mental havoc. It’s a reminder that even those who make us laugh the loudest could also be paying a heavy emotional price in the background.

I don’t wish that isolation on anyone, but I respect the mental fortitude it took to keep the world smiling while his own world was so quiet.

a slightly nicer cubicle working from home

His later-life polarization may well have been a symptom of a life spent in a “fabric box” of his own making. But to me, that doesn’t dim the light of the humor he shared for decades.

I’d like to end with a thought experiment. Smiles and laughter are key components of a good life. If you can laugh, there is joy in that moment, regardless of what else is happening. The person who creates that joy is a treasure. Special. To be celebrated.

How rich did Scott Adams make the world? What would the “Dilbert Joy Index” look like?

Dilbert syndication hit a potential peak of 150 million newspaper readers per day by the late 90s. With viewers seeing comics 365 days a year for 33 years his number of total views become staggering. Add in people who viewed his work on the internet, comics hung on the cubicle wall, and published in his 50 books and we are talking billion of views.

Assuming 1% of of viewers smiled or laughed at his jokes would have generated about 8.7 billion total smiles or laughs. I could argue his hit rate was closer to 10% of his views which would take it to 87 billion instances of little bits of joy.

To put it another way, on average, he made every human on the planet smile or laugh at least once.

In this way he brought immense joy to the world. He made our lives just a little bit richer every day. Very few people can claim to have generated that much happiness.

So, I say thank you, Scott. Thank you for the smile you put on my face and on the faces of countless others.

Onward in my hunt for Dilbert 34.

Leave a reply to timpiker Cancel reply